Once upon a time there was a girl. She lived at the edge of a forest where she took care of a young knight. The knight was her world, his travels were all that mattered, all that she could think of, in the peppermint painted shack where they lived.

The King had been taken from them by a dragon. There’d been no sparing, no rolling wars just the sound of its claws in the night, clicking down the pebbled path that they’d built years ago. And it came with its quiet smoke filled breath and its heat and its rage and stole him away in the night. It took him to its lair deep inside the woods, its cave with all its stone cold promises, the moss dripping the names of all the people he’d eaten before.

The girl continued in the shack because that was the path laid in front of her and the young Knight grew. His back grew stronger than hers, his own path flowing out from their home, merging with the girl’s and branching off. They continued to live at the edge of the forest, they collected twigs and rocks and made tiny sculptured shapes in the mud and rain.

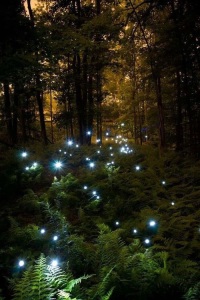

In the autumn of the fourth summer the Knight stumbled on a crag, he slipped, twisting his ankle until all he could do was limp to their shack and rest. The girl looked to the books on the shelves, she searched through velvet pages until she found the instruction for The Heal. And there in her small white hands the pages told her to search for the frond that would not age, and to bind it with twine around the injured ankle and then to wait. And she knew and her heart dropped far away as she read to the end of the page. There was only one frond in the forest and it grew at the back of a cave – the dragon’s cave. So she gathered up all of skirts, strapped her tiny feet into the leather boots shed cut and sewed from the King’s clothes and she scooped up the Knight, though he was twice her weight, she heaved him up on her fragile back and though terror charged throughout every vein, she strode out, small painful steps taking herself and the Knight back, towards the lair, deeper into the forest towards the part of their land that they never went near, there in the autumn, walking back right into the dragon’s claws.

And the small girl felt the bile bubble up in her mouth, her ribs pulling tight around her until every breath was an effort and every pulse beat louder than the last but she strode out.

The edge of the forest approached them, the Knight grew heavier but they carried on until the wind sliced across their cheeks, the brambles and spikes fell away and they stood, there, together in the memory of all that had gone before. The cave, the sound of the dragon sleeping and the stench, the saturating smell of yesterday and with stinging eyes and aching ribs, they breathed in.

The dragon was curled at the back of its lair, its scales opening and closing as it slept, its tailed flicked at the tip and its leaden eyelids twitched. The Knight held onto the girl, the girl clung onto the knight but did not speak. They knew there was no option but to walk in and around the stinking beast. They held hands and they walked, the Knight limped, leaning into the girl and the hours passed as they moved. And there came a time when they reached the back of the cave, where familiar sounds chipped into them, where every stone and every clump of moss echoed with the King’s voice and all they could do was sit and wait and watch for the signs to come to them. The Knight fiddled with his armour, the small girl smoothed out the creases in her skirts, they were sodden now, rivulets of moisture chundering down to her feet and they sat. The girl studied the floor of the cave, leaves blew in and out and creatures crawled. The dragon stretched in his sleep, half yawned as his tongue fell from his dripping pink mouth and scooped up a trail of insects that passed by underneath him. They were swirled up on the tiny bristles, scraped back into the hot steam of his jaws before they’d had time to think about it. And he swallowed and he slept.

In the distant corner of the lair they waited, the moss sweated, dust twisted in the last beam of light and the girl looked out. It was time. She didn’t know how she knew but she just did and she took the Knight’s hand led him up to the dragon’s mouth. And he knew too, he blew into its nostrils, disturbing it, rousing it until it sneezed and stood there, rippling fierce, the thunderous chasm of its mouth tearing wide before them.

‘We have to go inside,’ she said, ‘the frond is caught in its teeth.’

And they stepped onto its knuckles and time slowed down. And they clambered onto its jaw bone, dug in deep and hauled themselves up and in. There they sat, panting, breathing out in the rank swimming juice from yesterday’s meal. The small girl knelt up its teeth to catch her breath, they shone despite years of decay, they lit up her face as she paused and bent down to scoop the liquid from around her feet. She moved towards the Knight’s injured ankle and brushed the contents of its mouth around the broken joint and the old beast yawned.

‘I see it – I can see it,’ the Knight called out. ‘There at the back, by its throat.’

And she took his hand and they edged themselves further down his tongue. She tried not to think, she tried not to feel but images severed and lunged. She focussed on why they were there, on the Knight, on his broken ankle, while her heart beat charged with the knowledge of what had gone before. The heat of the the Knight’s hand formed a golden thread inside her, it kept her moving as they inched over the lumpen rancid route.

‘Over there, look!’ said the Knight and they saw, wedged between its molars, a single pale green leaf, battered and torn but still recognisable and they crept. The small girl’s skirts dragged around her, sodden with the moisture from its mouth, the young Knight kept moving forwards, his heavy armour clanking as he shifted behind his Mother and they breathed.

The Knight held on tight around her waist as she reached over, she trembled like their tiny shack shook when the dragon had approached, her heart thudded loud like its feet smashed down their path but she reached out. And with every cell in her ravaged form she stretched out, for her Knight, for their life, and with a surge of energy that welled up from her deepest oldest places, she curled her fingers round the frond and tugged. It was stronger than she’d hoped and the Knight pulled backwards more and the girl dug her nails into the stale flesh of the dragon’s gum. The vast beast winced at the prickle of pain, forming a gush of saliva to swell up pooling around the girl’s skirts, staining the Knight’s armour.

‘Again!’ said the Knight and she knew. And again she stabbed her golden nails into its flesh, and as more gunk swirled up around their limbs she pulled hard, using all the power she could muster in her small white hands.

The frond shifted, unfurled and slipped off the huge tooth, releasing the girl and the Knight. All three of them bounded backwards in a sweated ball, tumbling like the images in their heads, ricocheting off teeth and food as time started up once again. And the dragon finished its yawn. They were catapulted out and away dropping back into the soil of the lair –

with a thump and a cry that echoed through the forest, that shook the tiles on the roof of their home.

The dragon curled up, smacked its lips together and carried on sleeping. The girl pulled her skirts around her and brushed the dust from the Knight’s armour. They looked at the battered plant and as they did, it started to pulse, little sparks of golden green brushed up through it leaves, filling out its form until it sparkled and tingled, it glowed with growth, with force, there in the small girl’s hand.

The girl and the Knight and frond were joined together in the filth of the cave, their strength pulsing from one to the other and the more they looked at where they were the more they saw their journeys. The Knight’s armour began to glow where the patches of rust had slowed him down and he took the hand of the girl and said,

‘This way now, follow me,’ And he limped but less than before and the girl squeezed tight to the frond as the dragon stirred, its belly empty, its need for nourishment never far.

And they left. As quiet as they came, leaving the moments behind them, in the slime and stones of ancient things, carrying on out to the light.

The girl sobbed, the Knight flopped to the floor as she took the pulsing plant and wrapped it with ease around his ankle. The sap seeped into his fracture and over her hands until his limb was bound and secure. She pulled at strands of twine that grew around the trees they sat beneath and plaited them over the smoothed out frond. The colours had faded to a softened soothing pale, a green that formed a balm on their way, to their eyes and aching hearts. The Knight’s ankle started to heal.

Behind them the constant sound of the dragon preparing for his next feast and they left him with his caverns, with his greed and piercing fangs, moved away from the echoing sounds of their fear.

The sun pushed through the night clouds, as it does, casting tiny flecks of tangerine on the dew caked leaves around them. The Knight walked, his ankle stronger than before, the small girl stuck to his side, her skirts drying out in the warmth of the rays and she glowed. Next to her Knight, she walked in the forces that charged from his feet, in her ways, her knowledge, ancient and pure, as they made their journey home.

And through the speckled woods they followed their path, back to their peppermint shack

with its stories and its tales and they couldn’t speak. They had no need for language then, but it was there, in the look they gave to each other back in their darkest world, when they faced the dragon once again. And there, nestling, primed, underneath them was the endless gifts of the King, the murmur of their voices, the in-breath and the start of the roar.

There was a girl who lived at the edge of the forest where she took care of her Knight.

On the windowsill was a small clay vase shaped like double helix and growing up and out from the vessel was a soft green stem, uncurled fronds leaning towards to photons that filled their tiny home.

And they grew.

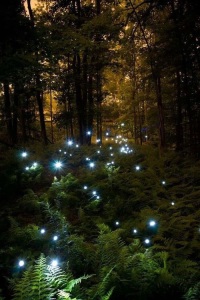

It was silent apart from the ticking of her clock, apart from the ringing in her ears. And in the garden, the edge of Autumn had begun. It crept in on the warmth of the leaves, in the morning sunlight making shadows on the wood. The door to the summerhouse was still open and in the reflection in its windows was the light pushing through her trees, there was a liquid ripple of her home and she was still.

It was silent apart from the ticking of her clock, apart from the ringing in her ears. And in the garden, the edge of Autumn had begun. It crept in on the warmth of the leaves, in the morning sunlight making shadows on the wood. The door to the summerhouse was still open and in the reflection in its windows was the light pushing through her trees, there was a liquid ripple of her home and she was still.